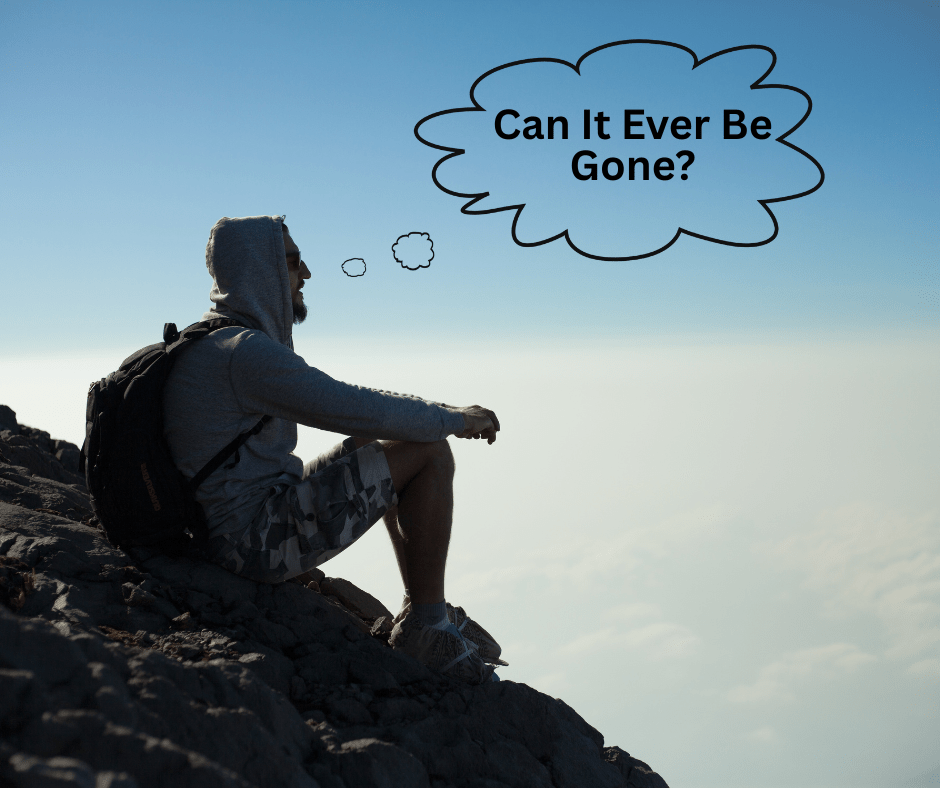

"Can It Ever Be Gone?”: Living Without Recurrence After Glioblastoma

I wrote this because, after 17 months of clean scans, I have yet to hear anyone say what I so desperately want—and fear—to believe: that maybe, just maybe, the cancer is gone. Diagnosed with glioblastoma in November 2023, I underwent gross total resection, completed radiation, took temozolomide, and wear Optune daily. My tumor was MGMT methylated. I have done everything right. And yet, no doctor will say the words. This silence led me to ask: When, if ever, is it appropriate to speak of remission in glioblastoma? This post is not just a clinical exploration—it is a deeply personal search for clarity, hope, and truth.

Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) remains one of the most aggressive and lethal forms of primary brain cancer. Despite advances in surgical techniques, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and adjunctive therapies such as tumor treating fields, glioblastoma is still characterized by its high rate of recurrence. However, in rare cases, a confluence of favorable factors can lead to a prolonged period without evidence of disease, raising the difficult and emotionally charged question: can glioblastoma ever be considered “gone”?

Statistically, glioblastoma recurrence is nearly universal. Studies indicate that approximately 90% of patients experience tumor regrowth, with a median progression-free survival of only 7 to 10 months following diagnosis (Vaz-Salgado et al.). Even with the full Stupp protocol—maximal safe resection, radiation therapy, and temozolomide chemotherapy—recurrence usually occurs within the first year (Eldridge). Therefore, any progression-free period that extends beyond 12 months is statistically unusual and places the patient among a minority of cases. For example, fewer than 15% of patients remain recurrence-free at 18 months (Mrvoljak et al.).

However, emerging data demonstrate that certain biological and clinical factors significantly influence prognosis. Chief among these are the extent of surgical resection and the tumor’s MGMT promoter methylation status. Patients who undergo gross total resection (GTR) have significantly longer survival compared to those with subtotal or partial resections, due to the minimized residual tumor burden (Cerullo et al. 586). Furthermore, MGMT promoter methylation is a strong predictive biomarker for responsiveness to temozolomide, with studies showing that median survival can increase from approximately 14 months in unmethylated tumors to over 21 months in methylated cases (Eldridge). When both favorable factors—GTR and MGMT methylation—are present, survival outcomes improve dramatically. One multicenter study reported that patients with methylated tumors and gross total resection had a median overall survival of 33.2 months (Mrvoljak et al.).

The introduction of Tumor Treating Fields (TTFields), specifically Optune, has also contributed to extended survival in newly diagnosed GBM patients. The EF-14 trial showed that the addition of TTFields to maintenance temozolomide increased median overall survival from 16 to 20.9 months, with a five-year survival rate increasing from 5% to 13% (Chmura). While modest, these gains suggest that multimodal therapy can shift the survival curve significantly, particularly in patients with otherwise favorable characteristics.

Case studies further support the possibility of long-term remission in selected patients. In one striking case, a 47-year-old man experienced multiple recurrences but ultimately achieved a complete remission after treatment with fotemustine, remaining cancer-free for over eight years (Cerullo et al. 587). Another case involved a 75-year-old woman with a methylated tumor who received two courses of hypofractionated radiation therapy and temozolomide. She remained alive and functional over 42 months after diagnosis, despite a recurrence around the 30-month mark (Mrvoljak et al.). These examples are rare but highlight that long-term remission—even following recurrence—is biologically plausible under specific conditions.

Given these data, it is reasonable to argue that a patient who has undergone gross total resection, has a methylated MGMT promoter, completed full chemoradiation and Optune therapy, and remains free of radiographic recurrence 18 months post-diagnosis is within a medically significant outlier group. This individual would already have exceeded median progression-free and overall survival benchmarks. In clinical terms, this patient could be categorized as a "long-term progression-free survivor." While physicians typically avoid declaring a glioblastoma “gone” due to the disease’s known tendencies for microscopic infiltration and late recurrence, there may be room—especially in such exceptional cases—for cautiously optimistic language.

Nevertheless, most experts in neuro-oncology hesitate to use definitive language such as “cancer-free” or “cured” in the context of glioblastoma. Dr. Peleg Horowitz, a neurosurgeon at Dana-Farber, explains that glioblastoma cells infiltrate surrounding brain tissue beyond what can be removed surgically or seen on scans, and therefore the disease can remain dormant before reactivating (Horowitz). Similarly, Chmura emphasizes that long-term survival is possible but rare, and that those who achieve it often share specific clinical and molecular characteristics (Chmura). The language typically employed is “no evidence of disease” (NED), a term that reflects the limitations of current imaging techniques and acknowledges the possibility of recurrence despite a clean scan.

In this context, it may be emotionally appropriate and medically justifiable for a physician to tell a patient that “the cancer appears to be gone” or that there is “currently no evidence of disease,” especially when reinforced with honest caveats about the inherent uncertainties of GBM. Statements of remission, when communicated with clarity and clinical backing, can offer hope without false assurance. For patients who have passed the critical 12- to 18-month threshold without recurrence and who possess multiple positive prognostic factors, the use of such language is not only justified—it may be therapeutic. The psychological benefits of recognizing a milestone in one’s cancer journey, even a tentative one, can support quality of life and emotional resilience (Eldridge).

In conclusion, while glioblastoma has a reputation for inevitability and recurrence, emerging data and case studies support the feasibility of remission in rare but well-defined circumstances. A combination of gross total resection, MGMT methylation, adherence to standard and adjunctive therapy, and sustained radiographic stability beyond 18 months forms a clinical scenario in which remission—though still statistically uncommon—is realistically achievable. While the phrase “the cancer is gone” must be used with nuance, it is not beyond the boundaries of responsible medical communication in select cases. Rather, it may mark a hard-won victory, however provisional, in a disease long defined by its relentlessness.

Works Cited

Cerullo, Carmine, et al. "Complete Remission and Long Term Survival in Recurrent Malignant Glioblastoma Treated with Fotemustine Monotherapy: A Case Report." Journal of Cancer Therapy, vol. 4, no. 2, 2013, pp. 584–587. https://doi.org/10.4236/jct.2013.42073.

Chmura, Steven. “Why Are Glioblastoma Tumors So Hard to Treat?” UChicago Medicine, 7 May 2018, www.uchicagomedicine.org/forefront/health-and-wellness-articles/why-are-glioblastoma-tumors-so-hard-to-treat.

Eldridge, Lynne. “Glioblastoma Recurrence: Incidence and Treatment Options.” Verywell Health, 16 Oct. 2023, www.verywellhealth.com/glioblastoma-recurrence-5205640.

Horowitz, Peleg. “Why Glioblastoma Is So Difficult to Treat.” Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, 7 Sept. 2021, https://blog.dana-farber.org/insight/2021/09/why-glioblastoma-is-so-difficult-to-treat/.

Mrvoljak, Midhad, et al. “Case Report: A Rare Case of a Long-Term Survivor of Glioblastoma Who Underwent Two Courses of Hypofractionated Radiotherapy as Part of Her Care.” Frontiers in Oncology, vol. 15, 2025, article 1501466, https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2025.1501466.

Vaz-Salgado, Maria Angeles, et al. “Recurrent Glioblastoma: A Review of the Treatment Options.” Cancers, vol. 15, no. 18, 2023, article 4579, https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15184579.

NEW ARRIVALS

NEW ARRIVALS APPAREL

APPAREL GIFT AND HOME

GIFT AND HOME COLLECTION'S

COLLECTION'S HOPE HUB

HOPE HUB BLOG

BLOG